The above artwork is from an unknown source. If anyone knows the identity of the artist, please drop me a line. It’s a great interpretation of a goddess who often looks more like a harpy in some of her traditional representations.

The attributes are all there, from the grain sheaves to the eight-pointed star, the horns of the Bull of Heaven, the lapis lazuli in her hair as well as the lunar symbols. Her gaze has something of hypnotic quality and there is something disquieting about the whole thing, with her dark, hollow eyes, she has a decidedly nocturnal countenance. She is fierce as well as strangely beautiful. There is nothing ornamental about her in the Venusian sense. She is the primary Sumerian goddess and Queen of the Night and Queen of Heaven.

If you’ve followed this blog over the last two years or so, you have seen me return to the theme of the early Middle Eastern, Sumerian, Babylonian and Pre-Islamic Arabian archetypes of the powerful Feminine deities which are more fully developed origins of Aphrodite and Venus. The record is very clear that what we consider the Classical deities associated with the planets and luminaries are the result of the devolution of original archetypes and, to some extent, made far more superficial than most astrologers realize..

This kind of research is problematic. We find that what is Classically known as Aphrodite and the planet Venus is represented in Sumer by a goddess that might be associated as well with planets other than Venus, including Mars and the Moon. There is also Sin, a male Moon-god, so the matter may become complicated in short order. Nevertheless, the Sumerian model is worthy of serious consideration in the quest for the essence of Venus.

The Classical Venus is not without nuance of course, but when we compare the understanding to Inanna, I think it safe to safe the archetype has been drained of much of its potency and the raw power of the Primal Feminine. Inanna, also known by the later Babylonian and Mesopotamian names of Ishtar and Astarte, is not primarily a goddess of love, but one who embodied war, wisdom, agriculture, sex, fertility, prostitution and lust, as well as a representative of the vegetative cycle itself and the traveller to the underworld. In Classical mythology, Mercury is the psychopomp, the guide to the Underworld.

Inanna is an active heroine. The recognition of the archetype immediately associated with Inanna goes as far back as far as 8,000 years.

Modern astrologers rarely, if ever, take into account whether Venus is the Morning or the Evening Star. We have a ‘one size fits all’ goddess who is prone to misunderstanding.

The Venus cycle is of crucial importance and to ignore that is to risk running amok in interpretations. The two primary phases of Evening and Morning star have very different qualities, but Inanna encompasses both in any case, making her a representative of the Feminine in all her guises.

Some Feminist astrologers have suggested that the goddess only took on the qualities of a warrior much later when the Middle East had become more violent. There are two problems with this.

There never was a time of anything much more than fleeting peace. The dream of an ancient society permanently at peace under a matriarchy is just that. In any case, in the earliest written work, Inanna is already a fully developed warrior of Heaven, the Earth and the Underworld.

She also demonstrates that there is no hell like a woman scorned, probably more than any woman before or since. In Tablet VI, Inanna desires King Gilgamesh, but Gilgamesh turns her down, citing the horrific fates of all her previous lovers. She goes into a blind rage and demands of her Father that she be allowed to release the Bull of Heaven t gore Gilgamesh to death. Her father refuses at first, pointing out that Gilgamesh might have a very good point. Her threats become ever more horrible and daddy eventually surrenders to her rage. In this, she can seem all too human, but she is in a trinity with the Sun and the Moon and she is of inestimable power.

It gets worse. The Bull is killed and Enkidu throws it back into the heavens to form a constellation, thus adding insult to injury.

It seems normal that her traits would display a degree of androgyny. She is courageous, quick-tempered, fertile and wrestles to create justice and balance in the most sublime, as well as the most savage.way. Her association with the scorpion and owls make her seem more like Lilith than Venus. In fact, Lilith is her adversary in the Sumerian creation myth. Lilith poisons the tree that Inanna had nurtured. More properly, we can say that Lilith is parasitic, as we shall see.

The poem begins: “when what was needful had first come forth,” when bread first started to be baked in ovens of shrines, and when the first separation occurred, that of sky and earth ” (Frayne 2001:130; Wolkstein & Kramer 1983: 4). A violent tempest uproots a huluppu tree, which Inanna rescues and plants in her own “sacred grove” at Uruk (Frayne 2001: 131).

Unfortunately, three beings settled in the tree: in its roots “a snake which fears no spell”; in its trunk a lilitu, a female spirit; and in its branches the Anzu bird.

Unable to rid herself of these intruders and parasites, Inanna is reduced to tears and calls upon her brother Utu, the sun god for help, but he refused, The hero Gilgamesh, Uruk’s warrior king, agreed to assist. Gilgamesh “smote” the snake, the others fled. Gilgamesh felled the tree, taking the branches for himself, The trunk was given to Inanna in a gesture that is difficult to fathom.

Presumably, it means that Inanna got the roots of the tree, In another version of the story, Gilgamesh uproots the tree, thus severing the connection of earth, heaven, and the underworld.

There are few passages in ancient literature that could out-do the erotic courtship of Dumuzi and Inanna and I’m certain there was never a better-crafted story of the descent to the Underworld on Tablet VI.. The imagery is stark., terse, vivid and terrifying. She is visiting her sister, Ereshkigal and makes elaborate preparation for the descent.

The following is from Table VI Descent Of Inanna Wolkstein – Kramer edition.

“Naked and bowed low, Inanna entered the throne room.

Ereshkigal rose from her throne.

Inanna started toward the throne.

The Annuna, the judges of the underworld, surrounded her.

They passed judgment against her.

Then Ereshkigal fastened on Inanna the eye of death.

She spoke against her the word of wrath.

She uttered against her the cry of guilt.

She struck her.

Inanna was turned into a corpse,

A piece of rotting meat,

And was hung from a hook on the wall….

Then, after three days and three nights, Inanna had not returned,

Ninshubur set up a lament for her by the ruins.

She beat the drum for her in the assembly places.”

She has become dead meat hanging on a wall. Her return to life by way of the intervention of Dumuzi is if course nothing short of a resurrection. With Venus in mind, we may well consider this as a metaphor for her stages of apparent and concealed visibility as part of her cycle The problem is first and foremost the specificity of three days from a culture well aware of the Venus cycle. In any case, the subject matter is quite unlike what we usually refer to as Venusian.

Quite simply, Inanna, Ishtar and Isis don’t have all that much in common with Venus at first blush. The Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Mercury and Saturn could all be described by her nature. In fact, the only luminary/planet that doesn’t fit is the Sun. By comparison, the Greco-Roman Venus seems rather thin and limited.

In the ancient Near East, Ishtar was an important and widely worshipped mother goddess for many Semitic* peoples. The Sumerians* called her Inanna, and other groups of the Near East referred to her as Astarte.

Inanna is a highly complex deity, combining the characteristics, both good and evil, of many different gods and goddesses. As a benevolent mother figure, she was considered the mother of gods and humans, as well as the creator of all earthly blessings. In this role, she grieved over human sorrows and served as a protector of marriage and motherhood. People also worshipped Ishtar as the goddess of sexual love and fertility. The evil side of Ishtar’s nature emerged primarily in connection with war and storms, much of it born of jealousy and rage. As a warrior goddess, she could make even the gods tremble in fear. As a storm goddess, she could bring rain and thunder, these events are now connected primarily to the Moon and Jupiter.

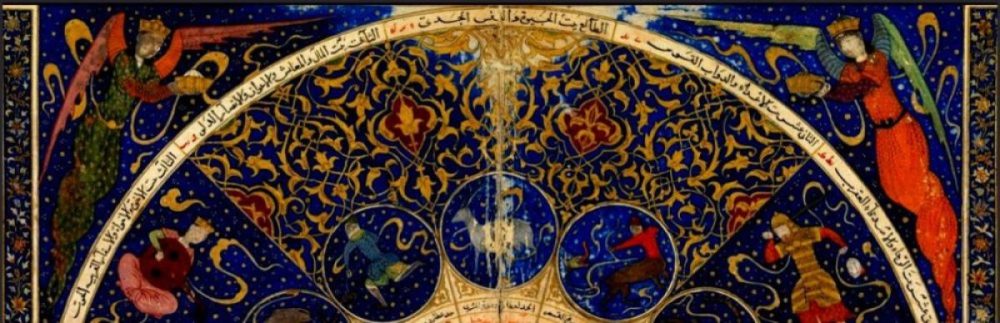

The eight-pointed star of Ishtar appears at top left, the crescent moon of the Moon God Sin is at top center, and the symbol of the Sun God

In the story of Inanna, she is the daughter of the male Moon god Sin and sister of the sun-god Shamash. Others mention the sky god Anu, the Moon-god Nanna, the water god Ea, or the god Enlil, lord of the earth and the air, as her father. Most myths link her to the planet, Venus.

There are a few things one can do with this comparison. The simplest and probably least disruptive would be to take a closer look at what we mean by our mythical association of Venus with the planet that bears her name and also what we mean by the Feminine. Venus is a goddess with tremendous limitations. But perhaps the greatest of these is that is not a mother goddess. Whereas earlier depictions of the feminine, whether it be Ancient Near Eastern or Celtic represented her in three phases: the Maiden, the Mother and the Crone, Venus pretty much remains on the first stage, allowing the Moon to take the other attributes.

Of course, astrology uses the Greek and Roman Pantheon as metaphors for the planets. However. it’s all too easy to forget that and our understanding of the planet itself is likely to suffer. The price paid during the advancement of civilization can be significant and I think it’s quite fair to say that the Greek and Roman Pantheon has little of the depth and earthy honesty of earlier cultures.

I’m certainly not suggesting that we give up on Venus, but we do well to remember the vast heights and depths that are found in abundance in earlier sources when it comes to a more complete representation of the Feminine. This article does little more than introduce some issues regarding Astrology and the Feminine. I hope it sparks some interest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.